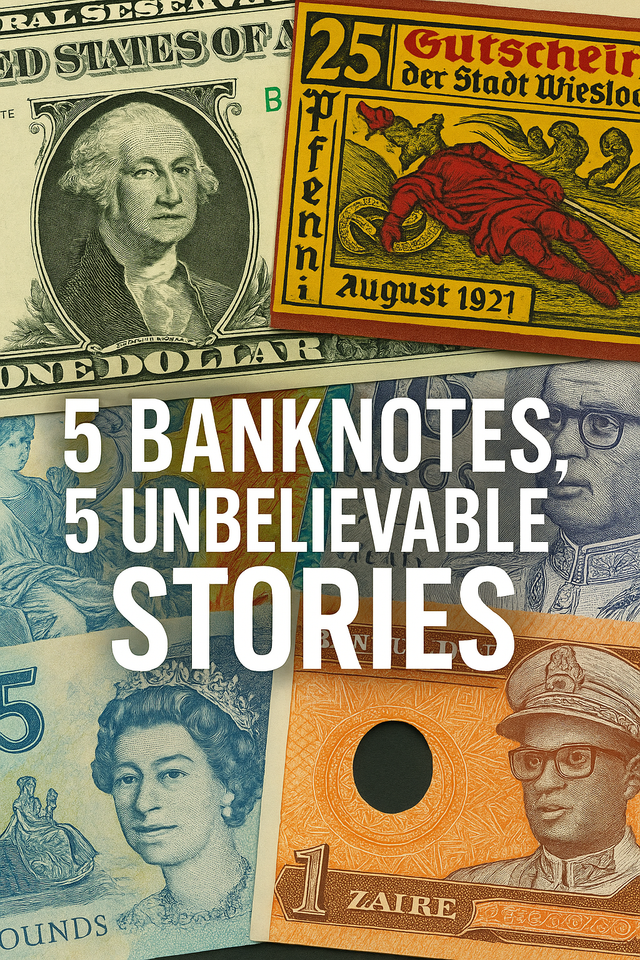

Pocket-Sized History: 5 Banknotes with Unbelievable Stories

It's more than just money. Every banknote in your wallet—or your collection—is a pocket-sized history book, a canvas for national identity, a witness to revolution, and sometimes, a comedy of errors. But some notes tell stories so unbelievable they sound like fiction. They are primary sources that tell tales of economic collapse, political defiance, royal scandal, and cultural clashes. These are not just curiosities; they are unique lenses through which to view history's most dramatic moments. Here are five notes with the most unbelievable stories ever told.

German Notgeld – The Beautiful Money of Collapse

The story of German Notgeld ("necessity money" or "emergency money") is a chronicle of a nation's descent into chaos, a tale told not in the halls of government but on small, fragile pieces of paper issued by thousands of towns across a collapsing empire. It is a story that begins with pragmatic invention, blossoms into an unprecedented explosion of folk art, and ends by feeding the very economic monster it was created to fight. Notgeld is a microcosm of the Weimar Republic's turbulent soul, a beautiful and tragic artifact of a society coming apart at the seams.

The Genesis of Necessity (1914-1918)

The first chapter of the Notgeld story was written not in ink, but in metal—or rather, the lack of it. During World War I, the German Empire funneled vast quantities of base metals like copper and nickel away from its mints and towards its munitions factories.

Notgeld.

These initial notes were, like their name suggests, born of pure necessity. Their designs were often simple, functional, and printed quickly to address the urgent cash shortage. They were a pragmatic, grassroots solution to a centralized failure, allowing local life to continue while the national state was consumed by war.

The Golden Age of Serienscheine (1920-1922)

As the war ended and Germany staggered into the uncertain peace of the Weimar Republic, the purpose and design of Notgeld underwent a dramatic transformation. Municipalities noticed a curious phenomenon: people weren't just spending the notes; they were saving them. Collectors across Germany and beyond were fascinated by this hyper-local currency.

This marked the beginning of the golden age of Serienscheine (series notes), which were often sold in complete, themed sets in specially printed envelopes.

This artistic flourishing was more than just decorative. In a period of profound national humiliation and political instability, with the central government in Berlin seen as weak and ineffective, this hyper-local currency was an act of cultural self-preservation. For small towns and rural regions, many of which are understudied by historians of the period, Notgeld was a way to assert their unique history, dialect, and identity in the face of national chaos.

A Canvas for a Troubled Nation

As the Weimar years wore on, Notgeld evolved again, becoming a raw and immediate medium for social and political commentary. The designs became a compendium of German memories, hopes, and fears.

Steckrübenwinter), a period of extreme food shortages, depicts a weeping turnip alongside the grim inscription, "Enduring hardship is the law of war".

This diverse output provides an unfiltered window into the German psyche of the early 1920s, away from the typical view of the Weimar Republic as defined by the liberal cabaret culture of Berlin.

Notgeld in 1923. He had only two days, but he seized the opportunity. His notes featured no historical or touristic themes. Instead, they were exercises in pure function, bold colors, and characteristic typography—an "aesthetic manifesto for modernism" delivered directly into the hands of the masses.

Notgeld gave the Bauhaus an unimaginable degree of public exposure, turning everyday currency into a vehicle for the avant-garde.

The Hyperinflation Catastrophe (1923)

By 1923, the German economy had entered its death spiral. The Weimar Republic was crippled by war debts and punitive reparations payments demanded by the Treaty of Versailles.

In this economic maelstrom, Notgeld returned to its original purpose as emergency currency, but on an astronomical scale. Notes were issued in denominations of millions, and then billions, of marks. Some surviving examples show notes where a value of "one Million Mark" has been stamped over and corrected to "five Billion Mark".

Notgeld was not a solution; it was fuel on the fire. The thousands of municipalities and businesses issuing their own unbacked currency in an unregulated frenzy created a tidal wave of worthless paper that swamped the economy. The decentralized printing of this "emergency" money became a major economic factor that actively contributed to and exacerbated the very runaway inflation it was meant to alleviate.

The story of Notgeld came to an abrupt end in November 1923 with the introduction of the Rentenmark, a new, stabilized national currency that finally tamed hyperinflation and made local emergency money obsolete.

Notgeld that survive are a vibrant, fascinating, and often beautiful visual record of one of the most tumultuous periods in modern history.

Zaire's "Ghost" Currency – Erasing a Dictator, One Hole at a Time

Among the pantheon of bizarre banknotes, few capture the imagination like the Zairean 20,000-zaire note with a conspicuous hole punched through the portrait of the nation's dictator. The popular story is simple and satisfying: when the tyrant was overthrown, the new government, short on cash, pragmatically kept the old notes in circulation by simply punching out his face.

The Reign of the Kleptocrat

To understand the note, one must first understand the man on it: Mobutu Sese Seko. For 32 years, from 1965 to 1997, he ruled the nation he renamed Zaire (formerly and now again the Democratic Republic of the Congo) with absolute authority.

A key pillar of his power was an all-encompassing cult of personality. His portrait, typically adorned in his signature leopard-skin cap, was ubiquitous. It hung in every public building, and most importantly, it appeared on nearly every single banknote issued during his three-decade reign.

The Fall of Mobutu (1997)

The end for Mobutu came swiftly. The 1994 Rwandan genocide sent shockwaves across the border, destabilizing eastern Zaire and igniting the First Congo War.

Deconstructing the Myth

It is in the chaotic aftermath of this collapse that the legend of the punched-out note was born. The banknotes themselves are real; collectors can readily purchase 20,000-zaire notes from the early 1990s with a neat, circular hole where Mobutu's face used to be.

First, the premise of a "cash shortage" is a fundamental misunderstanding of Zaire's economic crisis. The country was drowning in money; the problem was that decades of hyperinflation had rendered it worthless.

The Note as a Folk Artifact

If the government didn't punch the holes, who did? The most plausible explanation is that this was not an official act of state, but an unofficial, symbolic act of popular justice. The punched-out note is best understood as a folk artifact, a tangible piece of the revolution created by ordinary people. In the power vacuum that followed Mobutu's flight, anyone from a disgruntled citizen to a low-level bank clerk could have taken a stack of the old currency and performed this simple act of damnatio memoriae—the ancient Roman practice of condemning a reviled figure by erasing their image from public monuments.

This physical act of mutilation is a far more visceral and potent form of political erasure than simply issuing a new banknote. To violently remove the dictator's face from the very symbol of his power transforms an instrument of state propaganda into an object of popular defiance. It is a symbolic annihilation.

In the fractured, chaotic economy of 1997 Zaire, where different currencies circulated in different regions and a massive shadow economy thrived, these symbolically "liberated" notes may have even circulated briefly.

The Philippines' "Mickey Mouse Money" – A Puppet Government's Currency

During the Second World War, money became a weapon. In the occupied Philippines, a bitter economic war was fought on three fronts: between the Japanese invaders, the defiant Filipino populace, and the strategic Allied forces. At the heart of this conflict was a flood of newly printed bills that the local population, in a brilliant act of psychological resistance, derisively nicknamed "Mickey Mouse money." The story of this currency is a powerful lesson in how ridicule can undermine authority and how a simple, insulting nickname can be exploited to become a tool of military strategy.

Invasion and Economic Subjugation

The ordeal began just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, when Japanese forces began their assault on the Philippines, then a US-controlled territory.

A Nation's Quiet Defiance

The Filipino people, who had a strong sense of loyalty to the United States and were anticipating their promised independence in 1946, overwhelmingly rejected the legitimacy of the Japanese occupation.

This crisis of confidence, combined with Japanese economic mismanagement and the severing of the Philippines' vital trade links, sent the currency into a vicious cycle of hyperinflation.

bayóng just to go to the market.

Weaponizing Worthlessness

The Allies, planning their liberation of the Philippines under General Douglas MacArthur, recognized that the currency's worthlessness was a critical vulnerability. They devised a sophisticated two-pronged strategy to weaponize the Filipino people's sentiment and turn the "Mickey Mouse money" against the occupiers.

The first strategy was counterfeiting. The US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) undertook a large-scale operation to produce high-quality forgeries of the Japanese notes. By a stroke of luck, they located a supply of paper in the US made from the same native Japanese plants used for the originals, making the fakes highly convincing.

The second strategy was propaganda. Allied forces captured caches of genuine Japanese notes and overprinted them with a simple, powerful question in English: "The Co-prosperity Sphere: What is it worth?".

The choice of which currency to use became a life-or-death decision. In stark contrast to the worthless "Mickey Mouse money," local resistance groups and the Philippine government-in-exile printed their own "Emergency Circulating Notes," often called "Guerilla Pesos".

Canada's 1954 "Devil's Face" Note – A Royal Controversy

In the world of numismatics, a good story can be worth more than gold. No banknote proves this better than Canada's 1954 series, forever nicknamed the "Devil's Face" notes. The popular legend is one of palace intrigue and public scandal: a subversive engraver intentionally hid a demon in the Queen's hair, sparking immediate outrage that forced the Bank of Canada to recall and redesign the entire series. It is a thrilling tale of conspiracy. The historical record, however, tells a far more fascinating and nuanced story—one of artistic fidelity, a trick of the public's eye, a controversy that took years to ignite, and the deliberate myth-making that transformed a printing quirk into a collector's holy grail.

A New Queen, A New Currency

With the accession of Queen Elizabeth II to the throne in 1952, the Bank of Canada began work on a new, modern series of banknotes to be issued in 1954.

The "demon" was born from Gundersen's remarkable skill and faithfulness to his source material. In the Karsh photograph, the highlights and shadows in the Queen's elegant coiffure, just behind her ear, formed a particular pattern. When Gundersen meticulously reproduced these contours using the high-contrast, fine-lined technique of intaglio printing, an illusion emerged. To an imaginative eye, the swirling curls of hair looked unmistakably like a leering face, complete with pouchy eyes, a hooked nose, and grinning lips.

The Controversy That Wasn't

Contrary to the popular myth of immediate and widespread public outcry, the release of the new banknotes in September 1954 was met with relative silence on the matter of the Queen's hair.

Even then, the "outcry" was a whisper, not a roar. A newspaper article from April 1956 noted that "only four or five people" had officially brought the matter to the Bank of Canada's attention.

Table 1: The "Devil's Face" vs. The Modified Portrait

| Original "Devil's Face" Portrait (1954) | Modified Portrait (1956) |

|

A close-up of Queen Elizabeth II's hair from the 1954 banknote. The highlights and shadows in the curls behind her ear form a distinct pattern that, through pareidolia, can be interpreted as a leering face with a clear eye, nose, and mouth. This is the "devil's face" that sparked the legend. |

A close-up of the same area of the Queen's hair from the post-1956 banknote. The engraving has been subtly altered; the highlights have been darkened and filled in, breaking up the pattern. The illusion of a face is completely gone, resulting in a more uniform and less ambiguous depiction of the Queen's hair. |

The Birth of a Legend

The story largely faded from public view until 1959, three years after the modification. It was then that Allan Klenman, a director of the Canadian Numismatic Association, reignited the story in the press, but this time with a conspiratorial twist.

Klenman's story created the enduring myth of a grand scandal and, in doing so, manufactured a numismatic legend. The value of the "Devil's Face" note is a textbook example of supply and demand. The supply was cut short by the Bank of Canada's quiet modification, making the original printing run relatively scarce. The demand was then artificially created years later by the sensational, albeit inaccurate, story of conspiracy and controversy.

The Cook Islands' Fertility God Note – Currency Too Controversial for Use

On rare occasions, a government issues a banknote that is so bold, so unusual, and so unapologetically authentic to its culture that it becomes an international sensation. Such is the case with the Cook Islands $3 note. Featuring a nude woman riding a shark on one side and an anatomically explicit fertility god on the other, the note's perceived "controversy" is largely the product of a cross-cultural misunderstanding. It is, in reality, a vibrant celebration of Polynesian folklore and spirituality that, through its unique design and supposed shock value, became an unlikely and highly sought-after collector's item.

An Unconventional Banknote

The Cook Islands $3 note, first issued in 1987, was peculiar from its inception.

The obverse, or front, of the note depicts a scene from the legend of "Ina and the Shark".

The reverse side features a traditional fishing canoe, or vaka, alongside a carved wooden statue of the god Te Rongo.

A Clash of Values

The "controversy" surrounding the note stems from the depiction of Te Rongo. The image is faithful to traditional Polynesian carvings of fertility gods, which are often anatomically explicit. The carving on the banknote includes a prominent penis, an integral part of the deity's representation of life, creation, and vitality.

The controversy, therefore, is not inherent to the note itself but arises in the eye of the beholder. When viewed through a more conservative, Western cultural lens, the presence of explicit nudity and anatomy on official government-issued currency can be perceived as shocking or taboo.

From Controversial to Collectible

Ironically, the very elements that made the note "controversial" are precisely what cemented its fame and desirability. The combination of the odd $3 denomination, the beautiful and dynamic image of Ina and the Shark, and the "taboo" element of the Te Rongo carving made the note an instant, must-have souvenir for tourists and a prized item for numismatists worldwide.

Its popularity has had a direct impact on its circulation history. While the Cook Islands government withdrew its larger denomination banknotes in 1995 in favor of the New Zealand dollar, the beloved and high-demand $3 note was kept in circulation.

Conclusion: More Than Just Money

The stories of these five banknotes reveal a profound truth: currency is never just currency. These pocket-sized documents, so often overlooked in the transactions of daily life, are rich historical artifacts that bear witness to the triumphs and tragedies of the human experience. They have served as vibrant canvases for artistic expression in a time of national crisis, as seen in the beautiful and varied designs of German Notgeld. They have become tools for symbolic revolution and the grassroots erasure of a tyrant, as with the crudely punched notes of post-Mobutu Zaire. They have been transformed into weapons in a sophisticated psychological war, where the nickname "Mickey Mouse money" proved as potent as any bullet in the Philippines. They have acted as the stage for the creation of modern myths and legends, like the accidental "Devil's Face" that haunted the portrait of a queen in Canada. And they have served as bold, unapologetic declarations of cultural identity, as demonstrated by the Cook Islands' proud depiction of its folklore and deities.

Each note is a tangible link to the past, a story of the people who made it, the times that shaped it, and the messages—both intended and accidental—that it carries. They encourage us to look closer at the money that passes through our own hands, to see it not merely as a medium of exchange, but as a silent narrator of history.

Ready to own your own piece of history? Every banknote has a story. Start your collection today.

Explore Popular Articles

Gold $5,600 & The 2026 Refining Crisis: The Great Repricing

The Great Repricing: A Century of Precious Metals Volatility and the 2026 Systemic Refining Seizure...

Gold Hits $5,000: The 2026 Strategic Metals Market Report

STRATEGIC MARKET INTELLIGENCE: THE MONETARY BIFURCATION AND THE TANGIBLE ASSET PIVOT MONDAY MARKET...

The $17 Billion Signal: Iraq’s "Development Road" & The Dinar’s Path to Global Trade

Republic of Iraq: Strategic Economic Reintegration Currency Normalization Outlook (Q1 2026) To: Ins...