Hungary’s 1946 Hyperinflation: The Worst Inflation in History and the Fall of the Pengő

Post-War Chaos and the Seeds of Hyperinflation

In the aftermath of World War II, Hungary’s economy was in ruins. The war had obliterated roughly 40% of the nation’s wealth, with an estimated 80% of the capital city, Budapest, left destroyedbbc.com. Infrastructure was shattered – nearly half of rail lines were wrecked and many factories lay in rubbledailynewshungary.com. On top of this physical devastation, Hungary was burdened with hefty war reparations (pledged at $300 million to the Soviets, among others) and the ongoing costs of Soviet occupationsimtrade.fr. The occupying Red Army not only confiscated resources and goods as “compensation,” but even issued its own unbacked pengő currency in occupied areas, which flooded the money supply and aggravated inflationdailynewshungary.comen.wikipedia.org.

Politically, the post-war Hungarian government was weak and split. A “coalition” government in 1945–46 struggled to govern alongside the Soviet-backed Communists, and effective taxation was nearly impossible amid the chaosen.wikipedia.org. With tax revenues unable to cover war costs and reparations, the government resorted to printing money on an unprecedented scale. Some historians even argue that the Soviet authorities deliberately abetted Hungary’s monetary collapse to wipe out the middle class and destabilize the economy for political endsen.wikipedia.org. Whether by necessity or design, all the ingredients for runaway inflation were in place: massive economic loss, huge external obligations, a shattered tax base, and uncontrolled paper money issuance.

The Pengő’s Collapse: From Inflation to Hyperinflation

In 1945, prices in Hungary began rising rapidly – and then explosively. What started as high inflation soon snowballed into the worst hyperinflation in recorded historyen.wikipedia.org. By July 1946, Hungary’s inflation rate reached 4.19×10^16% for the month (41.9 quadrillion percent)en.wikipedia.org. In practical terms, prices were doubling about every 15 hours during that monthen.wikipedia.org. For comparison, even Zimbabwe’s notorious 2008 hyperinflation never quite surpassed this record, and Weimar Germany’s 1923 episode was orders of magnitude milderen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Hungarian inflation in mid-1946 was so extreme that whatever a person had in their pocket in the morning would lose half its buying power by the eveningbbc.com.

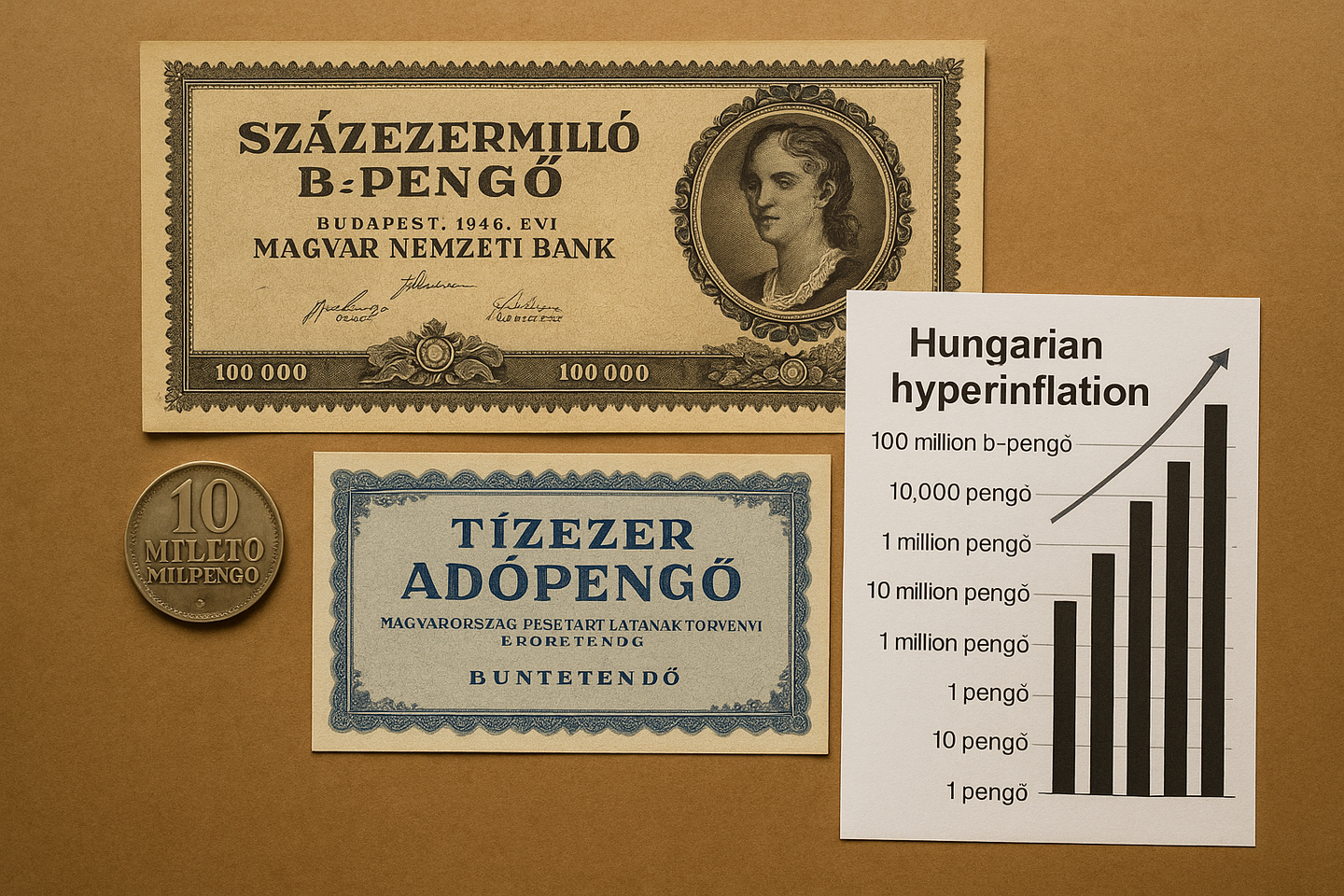

Several attempts were made to slow the inflation, but none succeeded. In late 1945 the government imposed a steep 75% “capital levy” tax on wealth, requiring citizens to buy stamps worth triple a banknote’s value and affix them to high-denomination pengő notesen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Unstamped notes became nearly worthless. This one-time tax temporarily reduced the money in circulation, but inflation resumed its upward spiral soon after. The authorities also tried to simplify accounting amidst the torrent of zeros by introducing new unit names for the currency. After the pengő had lost too much value to count, the government issued notes denominated in milpengő (short for millió pengő, or one million pengő) and later in b.-pengő (short for billió pengő, or one trillion pengő on the long scale)en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. These were not new currencies but rather naming conventions to cut down the length of numbers. Essentially, 1 milpengő represented 1,000,000 pengő, and 1 B.-pengő represented 1,000,000,000,000 pengő (one trillion in Hungarian long scale)en.wikipedia.org. This convention allowed the re-use of printing plates with just a color change and a new label instead of designing entirely new banknotes for every extra zeroen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Despite these efforts, the value of the pengő continued to plummet at a dizzying pace.

By mid-1946 the numbers became mind-boggling. In July 1946, the Hungarian National Bank issued the 100 million B.-pengő banknote, the largest denomination ever actually circulated in the countryen.wikipedia.org. This single bill was emblazoned “100,000,000 B.-Pengő,” which equaled 100 quintillion pengő (10^20 pengő) in ordinary termsen.wikipedia.org. It holds the grim record of being the highest denomination banknote ever issued for circulation in the world. (Even higher notes were printed in Hungary – a 1 “milliárd” B.-pengő worth 10^21 pengő, i.e. one sextillion pengő – but that note never made it into circulationen.wikipedia.org.) Tellingly, when the 100 million B.-pengő note was released in July 1946, its purchasing power was only about USD $0.20 in real valueen.wikipedia.org. In other words, a quintillion pengő could hardly buy a candy bar.

New denominations were rolled out at lightning speed. In April 1946, the highest note was 10,000 milpengő (10^10 pengő)en.wikipedia.org; by June, the highest was 1,000,000 milpengő (10^12 pengő)en.wikipedia.org; by early July, notes of 100,000,000 b.-pengő (10^20 pengő) were being printeden.wikipedia.org. Banknotes literally rushed out of the printers and into the streets, often with only weeks (or days!) between successive issues. Citizens eventually stopped referring to money by its face value – the numbers were too large to keep straight – and instead identified banknotes by their color or designbbc.com. For example, people might ask for “a blue note” or pay with “two reds,” since saying “100 trillion pengő” or “one quintillion pengő” had become almost meaningless in daily life.

The Adópengő: A Temporary Lifeline for a Failing Currency

Amid the currency free-fall, the Hungarian government introduced a parallel currency known as the adópengő (meaning “tax pengő”) in an attempt to stabilize daily transactions. Launched on 1 January 1946, the adópengő was originally an indexed unit of account – a way to quote prices and salaries in more stable terms by adjusting its value daily against the pengően.wikipedia.org. Initially, 1 adópengő was defined equal to 1 pengő. But with inflation roaring, the government would announce a new conversion rate each day (often via radio broadcasts) to keep the adópengő’s value roughly in line with pricesdailynewshungary.com.

For a few months, this strategy provided a modicum of stability. However, as the pace of inflation accelerated, even the adópengő couldn’t hold value. The exchange rate of adópengő to pengő had to be raised exponentially: by May 1, 1946, 1 adópengő equaled 630 pengő; by July 1, it was 7.5 billion pengő; and by July 10, a single adópengő was worth an astronomical 2×10^21 pengően.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. In essence, the adópengő was inflating almost as fast as the pengő – just with a slight lag.

Beginning in late May 1946, the Ministry of Finance started issuing adópengő paper bills (essentially tax credit certificates) in denominations from 10,000 up to 100,000,000 adópengően.wikipedia.org. These simple, low-quality notes were soon declared legal tender and circulated alongside pengő notesen.wikipedia.org. By the final months of hyperinflation, prices were commonly quoted in adópengő rather than pengő, since the regular pengő figures had become unmanageably hugeen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. In fact, adópengő notes almost completely replaced pengő in daily use by July 1946en.wikipedia.org. This maneuver did slow the inflation rate somewhat, by siphoning off some of the pengő in circulation, but it was far from a cureen.wikipedia.org. Both pengő and adópengő were spiraling out of control by mid-1946; the adópengő had simply provided a brief psychological and accounting stopgap.

One side effect of the adópengő scheme was practical: the enormous quantity of paper required to print all those tax notes caused a shortage of quality paper stock in Hungaryen.wikipedia.org. Ironically, this paper shortage impeded the printing of the new currency (forint) notes that were planned to end the crisisen.wikipedia.org. By July 1946, it was evident that only a radical currency reform could restore confidence. The pengő – once a proud and stable currency in the interwar years – was effectively dead.

Everyday Life During Hungary’s Hyperinflation

For ordinary Hungarians, daily life in 1945–46 was nightmarish. The pengő’s collapse wiped out the savings of an entire generation. People who had stored wealth in cash (as many did, since the pengő had been a trusted currency in the 1930s) saw those life savings become worthless virtually overnightsimtrade.frdailynewshungary.com. Middle-class families that had scrimped and saved were suddenly destitute. Everyone became a pauper at roughly the same time – a traumatizing experience that Hungarians summed up as “when money died.”

As cash lost its value by the hour, normal commerce broke down. A barter economy sprang up in its placesimtrade.fr. Goods became the true currency: city-dwellers would travel to the countryside lugging whatever valuables they had left – clothing, linens, jewelry, even porcelain – to trade for fooddailynewshungary.com. Farmers, understandably, refused to sell food for paper pengő that might be worthless the next day; they wanted tangible goods in return. Markets turned into swap meets where a pair of boots might be exchanged for a sack of potatoes. This barter system was inefficient and often inequitable, but it was the only way to survive when the national currency was “not worth the paper it’s printed on.” Indeed, photos from the time show banknotes being used as fuel for fires or as wallpaper, since they were more plentiful than actual fuel and cheaper than blank paperdailynewshungary.com. One striking image from 1946 shows a woman lighting her cigarette with a torch of pengő notes – a poignant demonstration that the money had more value as kindling than as currencydailynewshungary.com.

The prices of basic necessities soared to incomprehensible levels. For example, a loaf of bread that cost 6 pengő in August 1945 cost 8 million pengő by May 1946, and a month later in June it cost 5.85 billion pengő for the same loafdailynewshungary.com. Workers’ wages lagged hopelessly behind prices, despite employers increasing pay sometimes daily or even more frequently. Many employers resorted to paying workers in kind (with food or goods) or in adópengő tax bills, since cash was essentially useless. Pensions and fixed incomes were obliterated – by the time pensioners received their check and went to buy groceries, the prices had doubled or tripled.

Public services and businesses struggled to function. Shop owners couldn’t keep up with repricing goods every few hours, and many shops simply closed down. Restaurant menus were often left without prices listed, or prices were adjusted between a customer ordering and paying. Train fares and postage stamps were adjusted constantly; eventually the postal service started overprinting stamps with new, higher values, just as the bank had overprinted currency.

In such chaos, daily life was reduced to a frantic race to spend money as soon as one got it. There was a popular saying: “Spend your pengő before it loses its value by sundown.” People would literally run from their workplace on payday to the shops to purchase anything of real value (food, clothes, tools) immediately, because waiting even a day meant the cash would buy far less.

Socially, the hyperinflation was a great leveler – it erased distinctions between rich and poor (aside from those with hard assets or gold). Everyone was equally desperate, queueing up with bags or even wheelbarrows full of notes for the simplest groceries. Yet, remarkably, despite the desperation, Hungarian society remained largely orderly. There was little violent unrest purely over the inflation (partly because the war’s end and the political changes were even more immediately jarring). Still, the psychological toll was immense. Confidence in government and the financial system was shattered. As one Hungarian later recalled, “we had to learn that money can die, and when it does, pieces of paper are no substitute for bread.”

Stabilization: The Forint Ends the Crisis

By the summer of 1946, the only solution to this economic death spiral was currency stabilization and a complete reset. On August 1, 1946, the Hungarian government replaced the pengő with a new currency, the forint. The conversion rate was set at 1 forint = 400 octillion pengő (4×10^29 pengő)en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. In other words, 400,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 old pengő = 1 forint. This astounding exchange rate (dropping 29 zeroes from the pengő) effectively acknowledged the pengő’s utter worthlessness. To put it another way, all the pengő cash in circulation in mid-July 1946 – a volume around 7.6×10^25 pengően.wikipedia.org – was converted into only about 0.19 forint in total valueen.wikipedia.org. The entire money stock of the country became worth less than one-fifth of a forint (which is the equivalent of a few U.S. cents).

The government’s stabilization program did more than just introduce a new currency. It was a comprehensive plan that included drastic fiscal and monetary reformsbbc.com. Key steps included: halting the printing presses to stop any further increase in money supply; instituting new taxes (and enforcing collection) to cover government spending without inflation; and securing as much backing for the new currency as possible. The National Bank accumulated whatever hard assets it could – including recalling gold reserves that had been evacuated abroad during the war – to build confidence in the forintbbc.com. The forint was announced to be pegged to a stable basket of gold and foreign currencies, at least on paper, at a rate of 13.21 forints per gram of golden.wikipedia.org. (In practice, convertibility was not available, but the psychological effect of a gold-backed claim helped restore trusten.wikipedia.org.)

Importantly, by this time, the political situation had also shifted. The Communist Party was tightening its control, and a “new regime” effectively took charge of economic managementbusinessinsider.com. The authorities could enforce the tough stabilization measures with an iron hand. Wages were initially kept very low in forint terms (meaning a harsh adjustment for workers who had seen pay hikes in pengő, even if meaningless ones)businessinsider.combusinessinsider.com. But the populace accepted this as a bitter medicine to cure the hyperinflation. Prices were immediately reined in once the forint was introduced – and critically, people believed in the forint, something that could no longer be said of the pengő. With a strict limitation on forint issuance and newfound fiscal discipline, inflation fell to normal levels by late 1946, effectively ending the nightmare. The hyperinflation had lasted barely a year, but its impact would scar Hungary’s economy and psyche for decades.

Comparing Hungary’s Hyperinflation to Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe

Hungary’s 1945–46 currency collapse often invites comparison to other famous hyperinflations, especially Weimar Germany (1923) and Zimbabwe (2007–2009). All three episodes shared the common feature of paper money overproduction amid economic collapse, but there were important differences in causes and outcomes:

-

Causes: Weimar Germany’s inflation was driven by World War I reparations and government debt – the German government printed marks to pay war debts and support striking workers during the French occupation of the Ruhr, leading to inflation. In Zimbabwe’s case, the 2000s hyperinflation stemmed from peacetime economic mismanagement – land redistribution policies shattered agricultural output, GDP plummeted, and the government printed money to finance huge deficits and an expensive war in the Congo. Hungary’s situation in 1946 was more analogous to Germany’s: it was a direct aftermath of a world war, with heavy reparations and physical devastation forcing the state to print money for survivalen.wikipedia.org. One unique factor in Hungary was the presence of foreign (Soviet) forces, some of whom may have intentionally fueled inflation for political endsen.wikipedia.org. Neither Germany nor Zimbabwe had a foreign army on their soil forcing currency into circulation, so Hungary’s case stands out in that regard.

-

Severity: All hyperinflations are extreme, but Hungary’s was quantitatively the worst. At its peak, Hungary hit 41.9 quadrillion percent inflation per monthbbc.com. By contrast, Weimar Germany’s worst month (October 1923) was about 29,500%en.wikipedia.org – enormous, but millions of times smaller than Hungary’s peak. Zimbabwe came closer to Hungary’s scale: in November 2008 Zimbabwe’s inflation was roughly 7.96×10^10% (79.6 billion percent) per monthen.wikipedia.org. Even so, Zimbabwe never surpassed Hungary’s record – prices in Zimbabwe doubled every 24 hours at peak, whereas in Hungary they doubled in under 15 hoursen.wikipedia.org. The highest denominations tell the story: Weimar Germany’s largest note was 100 trillion marks (10^14)en.wikipedia.org, Zimbabwe’s was 100 trillion Zimbabwe dollars (10^14) in 2009en.wikipedia.org, but Hungary’s was 100 quintillion pengő (10^20)en.wikipedia.org, with an unissued note of 1 sextillion pengő (10^21) as well. Hungary wins the unhappy prize for the most hyperinflated money ever.

-

Outcomes: All three episodes ended by abandoning the hyperinflated currency. Weimar Germany implemented a successful currency reform in late 1923, introducing the Rentenmark (later the Reichsmark) backed by land values and gold, which swiftly stabilized prices. Hungary likewise introduced the forint in 1946, which remains Hungary’s currency to this day. Zimbabwe’s end was a bit different – after several futile re-denominations (chopping zeros off the currency), Zimbabwe in 2009 completely abandoned its dollar and adopted foreign currencies (like the US dollar and South African rand) for transactionsen.wikipedia.org. This effectively ended Zimbabwe’s inflation, though at the cost of surrendering sovereign monetary control. In all cases, once a new stable unit was established (or a foreign currency adopted), inflation stopped and the economy could begin to recover. However, the social and political ramifications differed: Weimar’s hyperinflation is often cited as contributing to social unrest that aided the rise of the Nazis. Hungary’s hyperinflation occurred right as the Communist Party was consolidating power; the economic chaos arguably made it easier for them to justify a tighter grip on the country (they portrayed themselves as saviors who fixed the currency, even as people suffered in the interim). In Zimbabwe, the ruling regime actually remained in power through and after the hyperinflation, though with significant reputational damage; dollarization stabilized the economy but Zimbabweans lost trust in their government’s currency for a long time.

Despite differences, a common thread among these episodes is that once hyperinflation starts feeding on itself, drastic action – essentially a currency reset – is the only way out. And in each case, the worthless notes from those periods have now become curiosities and collectors’ items worldwide, tangible reminders of the frailty of monetary systems.

Collecting Hyperinflation Banknotes: Pengő and Adópengő Today

For today’s currency collectors and history enthusiasts, the banknotes of the Hungarian hyperinflation offer a fascinating window into this dramatic era. What was once nearly worthless “hyperinflated money” is now sought after as historical collectibles. In particular, the highest-denomination B-pengő notes of 1946 and the peculiar adópengő tax notes attract significant interest. Collectors are drawn to them not for their (long gone) face value, but for their historical significance, novelty, and scarcity in good condition.

Some key considerations for collectors of Hungarian hyperinflation notes include:

-

Historical Significance: Every pengő or adópengő note from 1945–46 tells a story of economic collapse. Owning a 100 million B.-pengő note – the largest denomination ever used – is like holding a world record in your hand. These notes are tangible artifacts of the worst inflation in history, and serve as educational pieces about monetary policy gone awry.

-

Scarcity and Condition: Despite the trillions printed, finding these notes in excellent condition can be challenging. During the inflation, people handled notes roughly or carried them in huge bundles, and most notes were discarded or destroyed after the forint conversion. Lower denominations (like few-thousand or million-pengő notes) remain relatively common and inexpensive today, often seen in circulated condition. However, high denominations in pristine uncirculated condition are far scarcer. For example, the 1 milliárd B-pengő (1,000,000,000 B.-pengő, or one sextillion pengő) was never circulated, and surviving specimens or uncut sheets of that note are exceedingly rare. Collectors pay close attention to condition – notes with crisp paper, bright colors, and no folds can command a premium. Conversely, heavily worn notes, even of high denomination, are less valued.

-

PMG-Graded Examples: Many serious collectors seek notes that have been professionally graded and encapsulated by services like PMG (Paper Money Guaranty) for assurance of authenticity and preservation. PMG’s grading provides a 1–70 score of a note’s condition. It’s not uncommon to see Hungarian hyperinflation notes with high grades given their short circulation period – some were never actually used as money. For instance, an uncirculated 1946 1 Milliárd B.-Pengő banknote was graded PMG 64 Choice Uncirculated and highlighted as an exceptional piece of hyperinflation historyplanetbanknote.com. Similarly, notes like the 100,000 B.-pengő (100 quadrillion pengő) or the 10,000,000 B.-pengő (10^19 pengő) are sometimes available graded in the mid-60s (UNC) range. Having a PMG-certified grade adds confidence and can increase a note’s desirability, especially for the top denominatons where counterfeits are extremely unlikely but provenance matters. Some collectors also enjoy the special pedigree labels (for example, notes with a “Planet Banknote” exclusive PMG label, indicating they came from a notable source or collection).

-

Collector Demand and Value: The market for hyperinflation notes is global. Hungarian pengő notes, much like Zimbabwe dollars or Weimar marks, have a broad appeal – they attract not just banknote specialists but also casual collectors, history buffs, and even people who just find the concept of a “100 quintillion” note amusing. Prices for these notes vary widely by type and grade. Common mid-range denominations (say 10,000 or 100,000 pengő) in circulated condition might sell for just a few dollars as novelty items. But top-tier notes in high grade – like a 100 million B.-pengő in UNC, or a 100 million adópengő tax note in superb condition – can fetch significant sums due to their combination of rarity and significance. These notes are no longer valued as money, but as collectible historical artifacts, and their value has increased to many times more (in stable currency) than what they could buy back in 1946en.wikipedia.org. In recent years, there’s been growing interest as people realize these represent the largest denominations ever printed. This demand has kept prices on an upward trend, especially for professionally graded examples.

For enthusiasts looking to own a piece of Hungary’s currency collapse, there are many options. PlanetBanknote.com itself features a range of graded pengő and adópengő banknotes from the hyperinflation period. Collectors can browse through PMG-certified pengő notes from modest billions to the staggering hundred-quintillion pengő notes. Each comes with a story – often included in the item description – contextualizing its place in the hyperinflation timeline (for example, a note might be described as “issued July 1946, just weeks before the pengő’s demise”). Holding one of these notes in hand can be awe-inspiring: the design and printing are of high quality, belying the chaotic economic conditions during which they were produced, and the strings of zeros serve as a sobering reminder of how money can lose meaning.

Ultimately, Hungarian hyperinflation banknotes have an enduring appeal to collectors because they encapsulate a singular moment in monetary history. They are conversation pieces, educational tools, and cautionary tales all in one. Whether one is interested in the 100 Million B.-Pengő note as the “largest banknote ever”, or an adópengő note as a quirky relic of a failed monetary experiment, these pieces carry lessons about economics and resilience. And unlike in 1946, when these notes could barely buy a loaf of bread, today they are valuable in a very different sense – as collectible pengő banknotes treasured by those who appreciate their historical legacy.

(If you’re a collector intrigued by this extraordinary episode, consider exploring the selection of graded hyperinflation-era pengő notes on PlanetBanknote.com. These notes – once symbols of economic disaster – now survive as tangible history, waiting to find a place in your collection.)

Explore Popular Articles

The Possible Future of Venezuela's Current Economic Crisis

Venezuela at a Crossroads Economic Possibilities After the Capture of Nicolás Maduro In a move that...

The End of a Corrupt Narco-Regime in Venezuela: The Venezuelan Pivot (2026)

The Venezuelan Pivot (2026) Geopolitical Shock, Monetary Reconstruction, and the Asymmetric Value P...

More Than Money: The Tangible Assets Drawing a New Crowd

The New Golden Age of Collecting A Market Transformed by Youth, Technology, and Value For decades,...